Lessons on Robustness from Neural Networks Research

Neural networks are now deployed in safety-critical systems, and yet we understand their failure modes far less than we understand their successes. This article examines an acoustic system from the early 2000s that operated reliably under difficult conditions. The lessons from that project remain applicable to modern artificial intelligence systems. The underlying problems have not changed. Only the scale and complexity have increased.

Machine Learning for Acoustic Source Localization

In the early 2000s, I built an acoustic localization system. The objective was straightforward: determine the location of a sound source in a room using an array of microphones and transducers.

The problem presented significant challenges. Sound waves reflected off walls. Ambient noise was ubiquitous. The signals of interest were small and obscured by background clutter. If the system produced incorrect results, months of data collection would be wasted. Therefore, the system required reliable operation under realistic conditions.

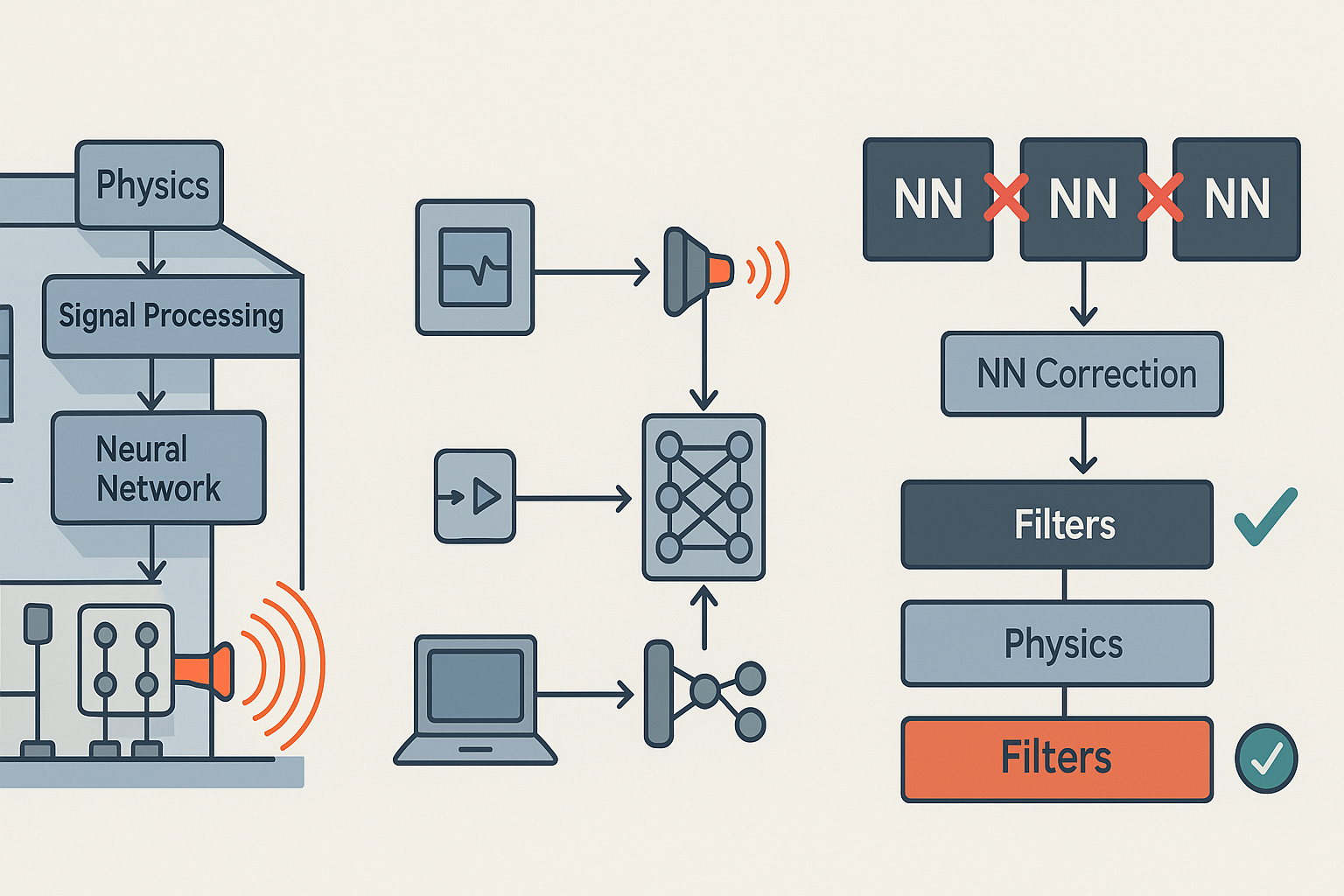

The system architecture consisted of the following stages:

- Record signals from all microphone channels simultaneously.

- Calculate time-of-arrival using phase information and the Fast Fourier Transform, leveraging the known microphone geometry.

- Filter out reflections and noise based on coherence measures, since true sources exhibit consistent phase relationships while reflections and noise do not.

- Employ a neural network to correct any remaining errors that the physics model could not explain.

The critical insight was that the neural network did not perform all the work. The physics and signal processing stages performed the majority of the processing. The neural network handled only the residual errors—the small corrections that the structural model could not compute.

This distinction is important because failures were predictable. If something failed, we could anticipate the consequences. The neural network was not an opaque black box making unexplained decisions. Rather, it was a well-defined correction layer built upon known physical principles.

Lesson 1: You Cannot Test for Everything at Scale

With the acoustic system, I could enumerate every failure mode that concerned us. These included broken cables, dead microphone channels, calibration drift over time, reflections from specific wall angles, and sudden impulse noise. We were able to test each of these conditions comprehensively.

Modern artificial intelligence systems operate under fundamentally different conditions. The input space is effectively infinite.

Vision systems encounter millions of distinct scenes under varying conditions. Language models process prompts written in unexpected ways by humans with diverse intentions. It is impossible to test all of these scenarios in advance.

This reality leads to an important conclusion: robustness is not achieved through exhaustive testing. Rather, robustness requires continuous adaptation and real-time monitoring.

Implementation considerations: Monitor the input distribution during production operation. Do not simply run the model on a test set once and conclude that validation is complete. Track statistical properties of the inputs: image quality, distribution characteristics, and confidence levels. When the world changes, the system should detect this change.

Establish fallback mechanisms. When the system encounters high uncertainty, it should fail safely. The system may either decline to make a prediction and escalate to human review, or employ a simpler baseline method. Explicitly acknowledging uncertainty (“I do not know”) is a valid system output.

Use production data as the primary testing ground. Log failures systematically. Label them accurately. Integrate these observations into system improvements. If the development team does not learn from real-world failures, the effort is not building robustness. Instead, it is simply building demonstrations.

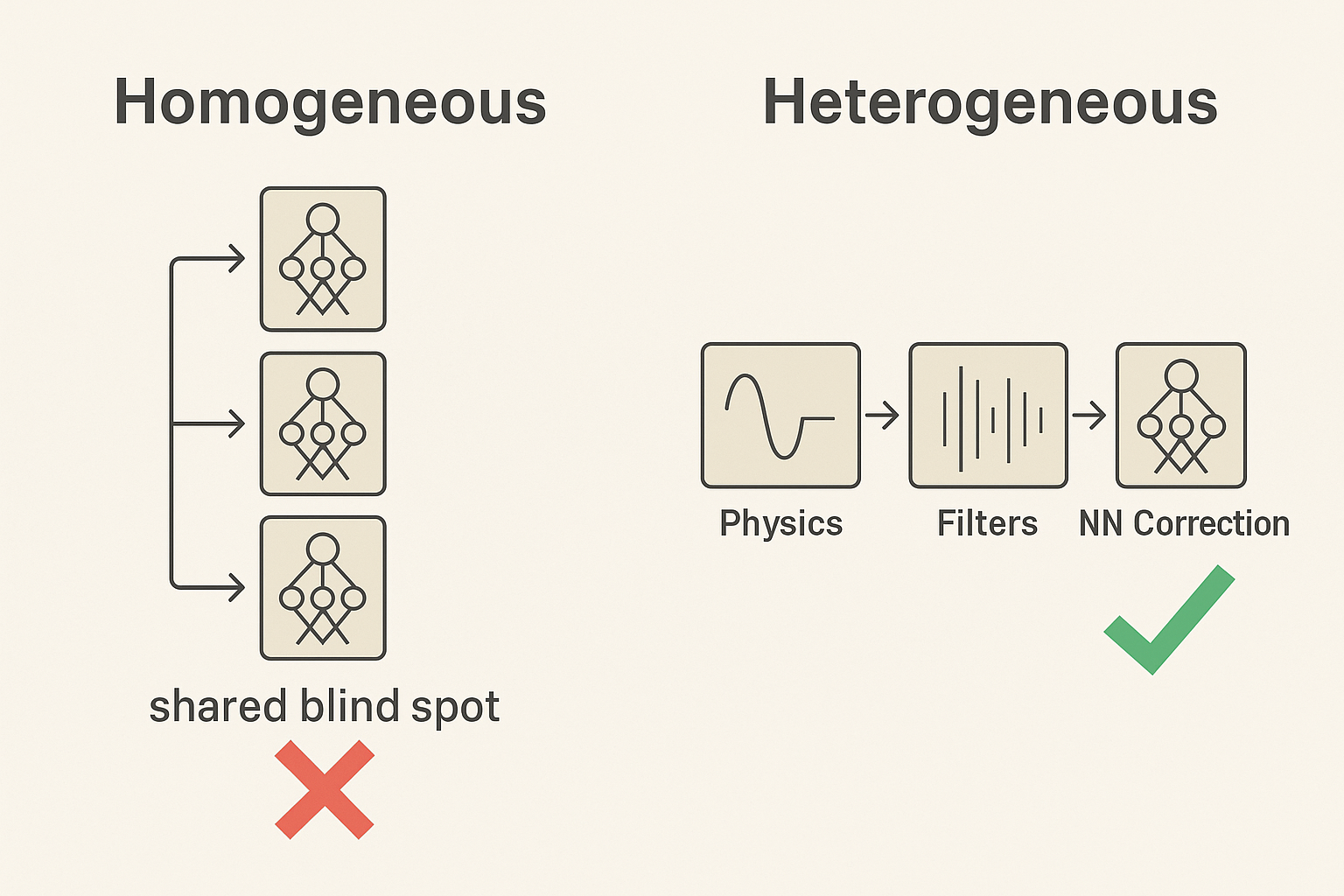

Lesson 2: Heterogeneous Systems Detect Contradictions; Homogeneous Systems Amplify Errors

Three identical neural network models trained on the same data do not provide safety guarantees. They fail together because they share the same inductive biases, the same data artifacts, and the same blind spots. Running three copies of the same model is not redundancy. It is merely confident error repeated three times.

The acoustic system possessed structural diversity, though this was largely accidental. The system contained three distinct layers:

- Physics layer: estimated source location using first principles of acoustic propagation.

- Signal processing layer: employed hand-designed filters to reject reflections.

- Neural network layer: corrected the small errors that remained after the first two layers.

This diversity in approach caught genuine failures in practice.

Consider the following example: Low-frequency reflections could create a false coherence peak approximately 30 degrees away from the true source location. The physics layer flagged this situation as ambiguous due to the presence of multipath propagation. The signal processing filters suppressed it because the false peak was less stable than the true signal. However, a neural network trained independently on similar data would confidently identify the false peak. The network had learned to exploit this pattern in the training data. The three-layer architecture detected this internal contradiction between the different components. Rather than reporting the incorrect answer, the system triggered re-measurement to resolve the ambiguity.

Without this architectural diversity, the incorrect answer would have propagated downstream without detection.

Application to modern systems: Combine different types of neural network architectures. Convolutional Neural Networks excel at detecting local spatial patterns. Transformer architectures excel at capturing long-range dependencies. Classical object detectors work well for known object categories. These different approaches fail in different ways on different inputs.

Do not rely entirely on neural networks for decision-making. Retain physics-based models, rule-based systems, and safety interlocks. Employ neural networks to refine or correct decisions, not to make all decisions from scratch.

When different system components produce disagreeing outputs, this disagreement is valuable information. It signals that something is unusual or problematic. Build systems that detect and escalate such disagreements rather than averaging them away.

Lesson 3: Architecture Determines What the Network Can Learn

Every neural network architecture encodes implicit assumptions about the problem domain. Convolutional layers assume that nearby input elements are related. Attention mechanisms assume that long-range dependencies are important to capture. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) layers assume that temporal order is fundamental to the problem.

These architectural choices are not neutral. They determine which patterns the network can learn efficiently and which patterns will remain effectively invisible to the model.

In the acoustic system, the structural choices performed the critical work:

- The microphone array geometry encoded rotation invariance directly into the measurement process.

- Signal processing stages reduced noise before the neural network received any data.

- The neural network received clean, structured input—not raw audio waveforms, but processed coherence values derived from the signal processing stage.

Contemporary machine learning practice often neglects these structural considerations. The prevailing approach is to employ large-scale models trained on large datasets and allow the network to discover all patterns autonomously. This approach can achieve high accuracy metrics. However, it often relies on brittle features that do not generalize when the data distribution changes in the real world.

The history of sequence modeling demonstrates this principle well. Long Short-Term Memory networks dominated sequence modeling from the 1990s through the 2010s. These architectures were specifically designed to maintain information over long sequences by selectively remembering or forgetting previous inputs. However, Long Short-Term Memory architectures have been largely replaced by Transformer architectures in recent years. Transformers use attention mechanisms instead of recurrent connections. They can process sequences in parallel rather than sequentially, which is more efficient. More importantly, Transformers achieve better performance on many tasks because attention mechanisms more effectively capture long-range dependencies than the gating mechanisms of Long Short-Term Memory. This transition demonstrates how better architectural assumptions lead to superior results.

Practical implications: Encode known invariances directly into the system architecture. If rotation, brightness changes, or noise should not affect the output, design the system to be inherently insensitive to these variations. Do not expect the learning process to discover these properties.

Apply domain-specific preprocessing aggressively. Use domain knowledge to shape the input before the learning process begins. In acoustics, apply frequency analysis. In robotics, enforce physics constraints. In structured databases, extract entities and relationships explicitly.

Maintain simplicity in safety-critical pathways. Emergency stop mechanisms, hard limits, and safety guardrails should be rule-based and interpretable. These should not rely on learned patterns. Neural networks should enhance these fundamental safety mechanisms, not replace them.

No amount of additional data will overcome fundamental misalignment between the architecture and the task structure.

Critical Questions Before Deployment

Before deploying a deep learning system in a production environment, the development team should answer the following five questions comprehensively:

1. What system components address the difficult aspects before the neural network receives input?

Does the system incorporate physics-based models? Does it implement rule-based logic? Does it employ signal processing or feature engineering? Alternatively, does the neural network start from raw input with no structural preprocessing?

2. Can different system components produce disagreeing outputs?

Does the system employ multiple types of models or multiple independent processing pathways? When these different components produce conflicting results, does the system detect and report this disagreement?

3. What assumptions has the system encoded into its structure?

Which problem characteristics should not affect the output? Examples include rotation invariance, robustness to brightness changes, or noise immunity. Has the system actually implemented these assumptions in the architecture, or does it rely on the learning process to discover them?

4. What happens when the system makes errors in production?

Does the system detect when it produces incorrect results? Can the system learn from these errors? Is there a mechanism to improve the system based on observed failures?

5. How has the system been evaluated for actual robustness?

Has the system been tested on corrupted, shifted, or adversarially challenging data? Or has the evaluation been limited to clean test sets that resemble the training data? Where are the results of these robustness evaluations documented?

If the organization cannot provide concrete answers to these questions, robustness should be regarded as an assumption made in the absence of evidence, rather than as a demonstrated property of the system.

Structural Principles for Robust Systems

Reliability in complex systems does not arise simply from small scale. Rather, reliability emerges from careful engineering decisions and deliberate architectural choices.

The acoustic system achieved reliable operation because it integrated three complementary approaches: physics-based models, intelligent preprocessing, and a neural network layer that addressed only the residual errors. The system benefited from architectural diversity. The system was evaluated extensively on failure cases, not merely on nominal operation scenarios.

Modern artificial intelligence systems should adopt the same principles. The neural network should not constitute the entire system. Instead, the neural network should be one layer within a broader system that also includes rule-based logic, physics-based models, safety interlocks, and real-time monitoring.

The fundamental approach is straightforward to state: Apply structure where the problem domain provides clear guidance. Apply learning where domain knowledge is insufficient. Apply measurement and monitoring everywhere.

Build systems anticipating failure modes and designing responses to them. Do not focus exclusively on optimal performance in idealized scenarios. Maintain human oversight and control until the problem domain reaches a maturity level where full automation is justified.

The systems that prove most resilient in real-world deployment are not necessarily those with the largest neural networks or the most sophisticated architectures. Rather, the most resilient systems are those that understand the boundaries of their knowledge, implement defenses against foreseeable failure modes, and maintain appropriate human involvement in critical decisions.

Technical references:

- Beye & Kim, “Interpretable Machine Learning”, 2019.

- Goodfellow et al., “Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples”, 2014.

- Bhatt, T. K. “Acoustic Source Location in a Noisy Environment Using a Microphone Array.” Tennessee Technological University, 1999.

- Bhatt, T. K., Darvennes, C. M., and Houghton, J. R. “Feasibility of Using Imperfect Microphone Arrays in Noise Source Location” Proceedings of the International Congress on Acoustics and Acoustical Society of America, Vol. II, pp. 13/17-13/18, Seattle, WA, 1998.

- Bhatt, T. K., Darvennes, C. M., and Ossanya, E. “Acoustic Source Location Using a Neural Network” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, Vol. 101, pp. 3057, 1997.